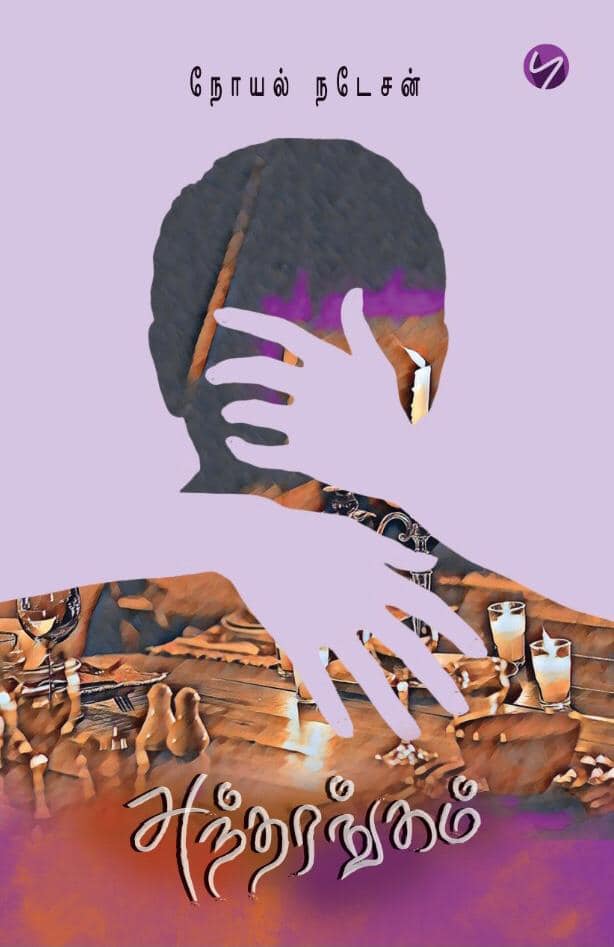

Short Story translated from Tamil and edited using Grammarly

Noel Nadesan.

My Palestinian mate and I were having a feed at a restaurant when he noticed how quickly I was eating and said, “Why are you eating like a suicide bomber? Eat slowly.”

When I was young and staying in a hostel, I used to gulp down my lunch and rush to the cricket ground. It wasn’t just me—every hostel student did the same. The boys who came from home would take their lunchboxes straight to the cricket field. But we, the hostel kids, had to go back to the dining hall; no choice. Our cricket matches would last more than five days. If we were late, the pillars on the boundary wall of Hindu College—which we used as stumps—would be taken by others. And since it was a wall, we didn’t need a wicket-keeper. That habit of hurried eating continued even at university.

Childhood habits stick with us like shadows—difficult to shake off even when we try to.

So when my mate compared me to a suicide bomber, his words stirred something inside me. Maybe he knew about them—perhaps he’d even met some. He had studied in Russia before seeking asylum in Australia. In my own country too, there had been suicide bombers. I’ve never spoken to any, but I’ve heard stories.

They say that before a suicide bomber goes on his final mission, he dines with his leaders. If it is the last meal of one’s life, shouldn’t one savour it? Why the rush?

The contradiction upset me. I was eager to learn more.

What must be going through the mind of a suicide bomber? When he sacrifices himself, does he truly believe, at least, that his death will contribute to a greater cause or value? Or is it merely loyalty to his leader?

Does he choose suicide because all other options to live freely in his society have been blocked? Or, like someone suffering from depression, does he opt for death because his mind collapses?

Humans will do anything to stay alive—even kill. Killing in self-defence is lawful. The Second Amendment in the United States guarantees the right to bear arms. Even a beggar is accepted by society because, after all, he’s begging to survive. Judges often show mercy to thieves who steal to get by. In ancient Tamil society, thieves were so integrated into the community that they were made into city guards.

Even murderers sentenced to death cling to hope until the very last moment, searching for that one reason to be spared. Modern jurisprudence dedicates its time and resources to finding the tiniest flaw that might save a life. In America, those on death row rarely face execution, as most countries have abolished the death penalty. Justice, law, medicine—everything in human civilisation aims to preserve life.

Human progress has always focused on safeguarding life and maintaining good health.

So how does a man who treats his life as fragile as a strand of hair—light enough to be discarded—still eat in a rush? Isn’t that contradictory? Or is the movement he belongs to deliberately trying to demonstrate to the world that its idealistic soldiers easily give up their lives? War heroes’ daily routines, martyr worship, poems praising death—aren’t they all propaganda aimed at taking someone’s life? War literature is simply preparation for killing innocent people.

There’s an even more fundamental question:

Only a man who values his own property will respect another’s. Likewise, how can a person who does not value his own life protect the rights of others? You can’t cite soldiers as an example here. A soldier, however bravely he fights, still wants to live. Even a wounded man clings to breath.

I’ve often wondered: if a suicide bomber was offered a green card to America, or a chance to enjoy a long and happy life with a beautiful woman—even just for a few days or weeks—would his mind change?

I longed to look into the eyes of a suicide bomber and understand his inner world. But that chance never came. Yet recently, I unexpectedly found myself reading the written testimony of someone who trained suicide bombers.

**“

I was born in 1984. After studying in Vavuniya, I went to Colombo in 2004 to study accountancy. Six months later, I visited Kilinochchi to see my unwell uncle. There, I was captured by the LTTE. They initially trained me in weapons. When they discovered I knew Sinhala, they assigned me to a special operations unit. There, I was taught how politicians and officials should be assassinated and how bombs should be detonated at the exact second.

But beyond that, I was taught psychology: how to endure torture, how to hide the truth, how to shadow someone without being noticed, how to earn trust, how to lie without ever slipping or contradicting myself. They said attachment to family and belief in God were weaknesses. Photographs of relatives and deities were taken away. Even my mother’s photo was removed—my trainer said it would make me cowardly.

After the training, I sensed a profound change within me. I could no longer laugh or speak freely. I forgot what friendship and affection felt like. Even in my dreams, my parents and relatives appeared less and less. Sometimes, the neighbour aunty would seem — and that too vanished. I wondered if I had killed all my emotions. Is this what sages attain?

Outside training hours, I spent my time alone. Even when others spoke to me, I couldn’t open up. I always feared someone was eavesdropping. Even when I was left on my own, I felt watched. When we watched videos of heroic missions, I felt a surge of pride—like fire rushing through my veins. I imagined myself inside those fighters’ bodies, soaring through dreams, believing I was part of some great ideal, that I would become a figure in history.

Around that time, I was sent to Colombo. But instead of heading straight there, I had to work in a hotel in Nuwara Eliya for six months.

From Batticaloa, I headed to Nuwara Eliya. As arranged, I found a job at a small tourist hotel with six rooms. My role was serving food.

It was there that I fell in love for the first time. That love was like rain in a desert—short-lived, but those few days felt like spring itself. In her innocence, Cecilia, the cook, stirred feelings that had long died inside me. She took me home to meet her parents. Her father was a farmer in Udapussellawa. Good people. But my conversations with them felt fake—I was trained to hide my actual thoughts. I couldn’t show what I genuinely felt.

I believe Cecilia’s innocence was what genuinely made me love her. I hesitated to take that love beyond a kiss. One day, while I was serving beer to a foreign tourist upstairs, Cecilia caught my hand on the staircase and gave me the first kiss of my life. I was drowned in that kiss, like standing under the first monsoon shower.

After that, every time I saw her on the staircase, my stomach tightened. I would silently pray that she wouldn’t be there when I climbed.

When the order to go to Colombo arrived, it freed me from her—but also broke me inside. I told her I had a chance to go overseas, and that I would write to her. She cried as she said farewell. I, who had always found lying easy, struggled immensely that day. I cried all the way to Colombo.

According to orders, I enrolled in an English class and stayed with a Tamil family in Dehiwala. While I enjoyed their company, I felt guilty about the danger they might eventually face. Colombo’s vibrant life charmed me. Meeting old friends, attending parties, hearing about their romances, meeting their girlfriends, going to beach clubs—it made me wonder why I couldn’t have a life like that with Cecilia. Why couldn’t I escape abroad with her? And above all, the words I had spoken to her kept haunting me like her kiss.

Then came the final command: prepare yourself for the operation.

The government was opening a new bridge in Colombo, and important people would attend. A suicide bomber was to be sent to plant the bomb. I was ordered to organise accommodation for him.

A boy came from Negombo—he looked about fifteen. When I asked, he said seventeen. I couldn’t believe it. I treated him like my younger brother, keeping him in my room. I bought him food. Looking at him, no one would think “LTTE”. He was chubby, with a round face, like a little Ganesha God statue. After every meal, he wanted ice cream. I didn’t ask where he came from or about his family. He had come to die—what was the point?

Apart from mealtimes, I avoided seeing him. The poor innocent boy…

I avoided meeting him except during mealtimes. The excuse that I was studying at the tutorial college made things easy for me. Like an innocent little boy, he stayed inside that room the whole time. I had bought many magazines and English pamphlets, and he kept looking at them.

When he kept flicking through the magazines again and again, I asked him, “So, have you finished reading everything?”

Nah, brother… I don’t know how to read,” he said.

……………………………..

Two days before the bridge opening, the suicide vest intended for him arrived.

The Tamil newspaper had reported that they planned to open the bridge at ten o’clock. We fixed the suicide vest under his clothes and took him out by eight. The boy who was already stout looked even bulkier with the bomb strapped on. I thought of telling him this, but my heart didn’t allow it. He wasn’t in a mood to appreciate humour. One small mistake, and not only his life but mine too, would be gone. As far as the Movement was concerned, my life carried more value.

When I bought him parotta with mutton and chicken curry at a Muslim hotel in Wellawatte, he devoured it with great relish.

Brother, when I ate with the Leader, the food was good. But I was scared to eat. And the cameraman kept telling me — look this way, look that way. I couldn’t eat properly. Seeing that, even the Leader didn’t eat much that day. Only today am I able to eat properly and enjoy the taste.

I listened to him with sympathy. Without replying, I stroked his swollen face and bought him a vanilla ice cream.

Since the bridge was due to open at ten, we were told to arrive half an hour later. One reason was that security checks would be lighter.

Vehicles had already been stopped, so we walked towards the place where the bridge-opening ceremony was to be held. It was morning, and many people were heading to work along the empty roads, so no one suspected us. All vehicles were halted and searched one by one after making them wait for several minutes.

“Walk slowly, brother. It’s hard to breathe,” he kept saying.

When we stopped near the giant cut-outs outside the theatres, I saw his eyes open wide, and a faint smile appeared on his face. It was no surprise — he couldn’t read, so cinema naturally meant more to him. I wondered how they picked a boy so small and innocent. He said he couldn’t read — what kind of family did he come from?

A wave of sympathy for him washed over me, and my eyes welled with tears. The last time I cried was when I parted from Sicilia after joining the Movement. This was only the second time.

We reached the place where the bridge was to be opened. Crowds of people had gathered along the street. How many were going to die here? Since many Tamils lived in this area, many of them would die too. More than that, how many would be arrested by the police today and subjected to torture? Even I could be caught today, or in a few days.

Near the bridge, hundreds of army and police personnel stood. Among them were men in white national dress who looked like politicians. Surrounding them, shielding them, were army officers. We had to push this boy into their midst and make him explode. I had to remind him of the Ammān’s constant warning: only if he pressed his face to his chest when he detonated would his head be destroyed and his identity erased.

As we moved through part of the crowd, a white man stood with a garland around his neck. He stood out — clearly a chief guest.

What a lot of trouble this had caused! We weren’t allowed to kill any foreigners during our operations. If foreigners died by accident, the government would easily use it as propaganda against the Movement. There was a strict order about this.

We decided we must call Ammān no matter what. “Stop, little brother. I have to speak with the higher-ups,” I told him.

“Tell Ammān to trust me,” he said, tears welling in his eyes.

I signalled to him with my hand not to speak, called Vanni, and said, “Ammān, there is a white man in the crowd.”

“Wait. We’ll check and tell you, “He replied.

Those five minutes felt the longest in my life, like a railway track stretching endlessly with no end in sight. When I was on the phone, a few people turned and looked at me. I spoke softly in Tamil and then loudly said a few words in Sinhala so Ammān would understand.

My phone buzzed silently.

When I answered, he said, “He’s an ambassador from a major country. He’s the chief guest and got delayed. Cancel the operation immediately.”

Ammān, we can’t leave this place. We’re surrounded by security.

To make it appear as if we halted the operation because of him, tell the boy to crash into a wall and explode.

The call ended.

How was I supposed to tell him this? But I had to.

Little brother, Ammān has cancelled the operation. Because a foreign diplomat is here, he says no. But he has instructed that you should detonate against a wall where no one else will die.

I couldn’t face his face as I said it. I turned away.

“Tell Ammān to trust me,” he said.

Nothing reached my ears after that.

“Tell Amman to trust me”—those words echoed again and again.

………………

After reading that confession, I felt I understood suicide warriors a little better.

பின்னூட்டமொன்றை இடுக