When the Tamil Medical Centre was founded in Chennai, Dr. Jayakularajah—who had escaped from Welikada prison—served as its president, and I was the secretary. Five militant organisations were affiliated with us. For a year, this joint effort ran smoothly without major issues. Our medical services reached both cadres and refugees alike. The collaboration also helped us develop strong relationships with Indian doctors and political figures.

Funded by overseas Tamils and charitable organisations, the Centre was preparing for its first annual general meeting in early 1986, marking a year since its inception. The meeting was scheduled for 10 a.m. at our office on the upper floor of 144 Choolaimedu High Road. As secretary, I had arranged everything. About half an hour before the meeting, I sent Karunanidhi—who was helping us at the time—in an auto-rickshaw to Mambalam to bring the president.

It was the first time we had ever sent a vehicle for the president. Usually, I wouldn’t have done so. But something in my gut told me he might not turn up. By the time the clock struck 10, our vice president, Dr. Shanthi Rajasundaram, had already arrived, and representatives from all the affiliated groups—except the LTTE—were present. We were waiting for the president.

From the second floor, above the noise of the street and passing cars, I heard the slap of Karunanidhi’s sandals on the stairs. I listened for a second set of footsteps, but none followed. Karunanidhi appeared alone.

Looking up at us, he said, “Doctor says he has to visit the refugee camp in Seyaru, near Chengalpattu. He doesn’t have time to come.”

Everyone was visibly shocked, though no one spoke. It was strange for a president to miss his own organisation’s annual general meeting. While others seemed surprised, Dr. Sivanathan and I, who handled the Centre’s finances, were less so. Still, the president’s indifference stung.

At the time, we already knew that Ms. Adele Balasingham was distributing medicines at two cyclone relief shelters near Chengalpattu, and that Dr. Jayakularajah was accompanying her. We had assumed he was doing so in a personal capacity. We never imagined he would abandon the organisation he was leading. We didn’t tell the others about this. Instead, Dr. Shanthi Rajasundaram chaired the meeting. Shortly afterwards, Dr. Jayakulrajah formally resigned, and she became our new president.

Dr. Jayakularajah was a man of great integrity and quiet compassion. He never raised his voice. I still fondly remember the time I spent working with him. However, we never received a clear explanation for his actions. Later, he became the head of the Tamil Rehabilitation Organisation (TRO). When I once asked him, “Why did you leave like that? Couldn’t you have told us before resigning?” he replied, “I was indebted to my brother (Prabhakaran).” Since we didn’t know the full context, we didn’t judge him too harshly.

It’s worth noting that the Tamil Medical Centre’s beginnings were funded by a ₹12,000 donation from my brother-in-law in the United States. He transferred the funds directly to Dr. Jayakularajah, instructing us to open an account at the Kodambakkam branch. In that sense, Dr. Jayakularajah was not just the president—he was a key stakeholder in the venture.

Following these events, the Tamil Rehabilitation Organisation was established with Dr. Jayakularajah as its leader. He owned a white van, and through this vehicle, the LTTE allegedly received ₹30 million of the ₹40 million raised by the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister for Eelam Tamil relief—according to a Dinamani report that included photographic evidence. TRO would subsequently become the main channel for overseas fundraising for arms purchases.

After I moved to Melbourne, Dr. Joyce Maheswaran served as the international president of TRO and later joined the LTTE’s peace delegation in negotiations with the Sri Lankan government.

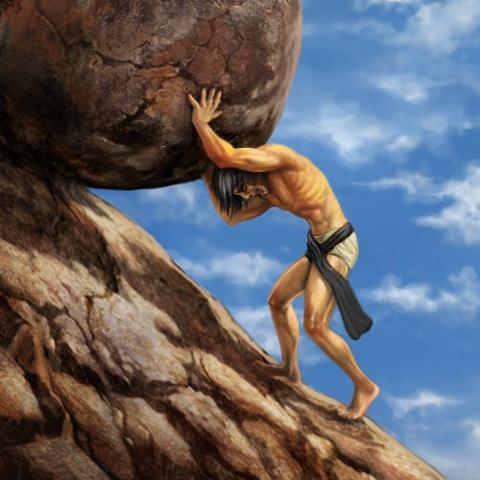

The Tamil Medical Centre—initially formed by five groups, including the LTTE—was effectively hijacked. The LTTE established TRO with our former president. From then on, tensions grew between factions. While other groups got caught up in internal conflict, they failed to notice the spark igniting within our organisation. I share this story to illustrate how that fire started. Politics is like a ship in stormy waters—those who ignore subtle signs will not survive.

Even after the LTTE ceased attending our monthly meetings, we kept providing services to many refugee camps. However, TRO now regarded us as rivals.

Most of the early refugees who arrived on Indian shores came from the Mannar coastal belt and nearby agricultural areas—communities with deep historical links to India. Forced out by increasing military and naval operations, they were soon followed by a wave of Tamils from Trincomalee by late 1985, many of whom were either sympathetic to or affiliated with the LTTE. These families were initially housed in cyclone shelters in Nagapattinam. The Tamil Medical Centre stepped in to provide first aid training and appointed two young men from Trincomalee as full-time caretakers.

One morning, one of them—Ravi—approached me and said, “The LTTE has told us not to come to the camp anymore. TRO will take over. But the people still prefer us. One woman told me that someone claiming to be Prabhakaran’s uncle insulted her in public, saying only that they were now in charge. We got scared and ran.”

What kind of situation was this? Had our medical service become a problem for the LTTE? I was frightened—but couldn’t show it. I was still the secretary. I had to stay calm.

“Who’s in Nagapattinam now?” I asked him.

“Dr. Jayakularajah,” he replied.

“Fine,” I said. “Let’s speak with him.” I sent word through the camp that I would come on Friday to resolve the matter.

We departed a day early—on Wednesday. By 5 a.m. Thursday, Dr. Sivanathan, Ravi, and I had reached Nagapattinam and knocked on the door of Dr. Jayakulrajah’s hotel room.

We didn’t want news of our visit to leak out. Back then, rivalries were deadly serious. Members of TELO, PLOTE, and the LTTE had all drowned rivals at sea. Indian intelligence kept track of violence on land, but sea killings often went unnoticed. We learned this from contacts within Indian intelligence.

We were filled with fear. The film playing on the bus hardly registered—we were lost in our own thoughts. None of us had shared this anxiety with our families.

When we arrived at the Nagapattinam bus stand, dawn hadn’t broken yet. Only a few tea stalls were open. After having some tea, we went to the hotel and knocked. Dr. Jayakularajah opened the door, startled.

“What’s this? So early in the morning?” he asked.

We had some other work as well, so we thought we’d get it all done at once. We knew you’d be here early.

“Come in.”

“Doctor,” I said, “you know we’ve been working in these camps since your time…”

“They cannot talk properly,” he said.

We’re overseeing five of the ten camps. Let us keep going. We’re not here to argue. If TRO wants to control everything, we’ll shift to another district.

“Fine, you handle five. I’ll speak with them.”

As he left the room, Ravi whispered, “That’s the man who chased us away—Prabhakaran’s uncle.”

I turned and saw the man glance away. I still remember: his white shirt tucked above a round belly, his blue-striped sarong pulled up to the knees, and his hairy legs.

Later, Nathan, who was then-secretary of TRO, told me, “Come to Jaffna—we’ll take care of you.”

I grinned and strolled off.

For two years after that, every time I saw a white van in Chennai, I instinctively looked for a side alley to avoid it. The LTTE had monopolised not just the war, but Tamil welfare too. That monopoly eventually spread across the diaspora.

Many of those who carried out this intimidation are no longer alive. But their techniques are still etched in memory. We might want to forget the past, but can we ever truly erase it?

பின்னூட்டமொன்றை இடுக